Studies show that high levels of anti-sperm antibodies (ASABs) have a negative impact on fertility and is also sometimes known as ‘Immunological Infertility’. Clinically significant levels of ASABs are found in the semen of 5–15% of infertile men, but in only 1–2% of fertile men. Some of these antibodies can also be found in blood and cervical mucus, although it is the level of certain antibodies in semen which have the biggest impact on fertility. As a result, Fertility Solutions performs an ASABs test with every semen analysis.

How Sperm Antibodies Are Formed

Seminal ASABs generally develop as a result of a breach of the blood–testis barrier (through trauma or surgery) or from obstruction of the male reproductive tract. Typically, high levels of ASABs are found in men with a history of testicular torsion, testicular surgery, vasectomy and inflammation of the male genital tract. Other conditions associated with ASABs include testicular cancer, history of undescended teste(s) (cryptorchidism) and some sexually transmitted infections.

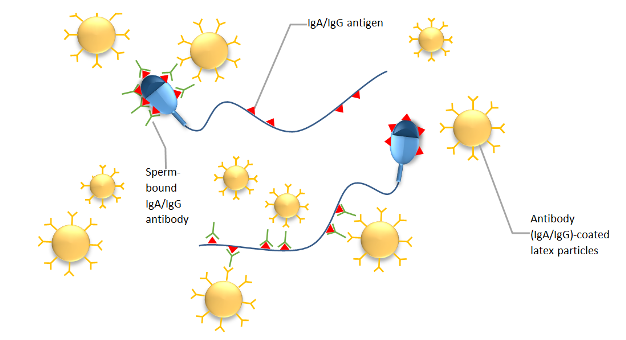

Like any other kind of antibody manufactured by the body, ASABs are formed in response to antigens. These antigens are proteins located on the outside of sperm (see image below). Once sperm and blood come into contact, specific antibodies are produced against the sperm antigens. The three main types of ASABs produced are Immunoglobulin G (IgG), Immunoglobulin A (IgA) and Immunoglobulin M (IgM). IgM antibodies, because of their large size, are rarely found in semen, while IgA and IgG antibodies are thought to have greater clinical importance and are both present in semen.

Once sperm antibodies have formed, these antibodies bind to the proteins (antigens) on the sperm head, mid-piece or tail and can affect sperm in several different ways. Some antibodies can cause sperm to stick together (agglutinating antibodies). Agglutinated sperm clump together in huge masses and are unable to migrate through the cervix and uterus. Other antibodies mark the sperm for attack by Natural killer (NK) cells of the body’s immune system (opsonizing antibodies). Some antibodies cause reactions between the sperm and the cervical mucus preventing the sperm from swimming through the cervix (immobilizing antibodies). Antibodies can also block the sperm’s ability to bind to the zona pellucida of the egg, a pre-requisite for fertilisation.

Our Method Of Testing

At Fertility Solutions, we use the Indirect Mixed Anti-globulin Reaction (SpermMAR) Test to detect antibodies present on the sperm surface. In this test, we combine IgA or IgG antibody-coated latex particles with the male patient’s sperm and count the number of sperm that have these particles bound to them. The World Health Organization considers a patient to have a clinically significant positive ASABs if more than 50% of sperm are bound. We recommend all male patients have a semen analysis prior to treatment, performed by our laboratory, which includes routine screening for IgA and IgG ASABs. This ensures that a patient is referred for the best and most suitable infertility treatment, in an attempt to achieve a pregnancy in the quickest possible time.

The presence of clinically significant levels of ABABs are not themselves an absolute cause of infertility. Even though ASABs reduce fertility, they do not prevent conception if a sperm is able to reach an egg. However, if a male patient has clinically ASABs, there is very little chance of impregnating their partner through natural ways.

Conclusion

Once a male patient has had a clinically positive ASABs test, it will usually be recommended that the best option to maximise that chances of fertilisation is intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). This is where each egg is injected with a single sperm. Fortunately, ICSI has optimized pregnancy in cases of male immunologic infertility, to the point that success rates are virtually unaffected by the presence or concentration of ASABs.

References:

FertiPro. (2014). SpermMar IgA/IgG Test. Retrieved from https://www.fertipro.com/inserts/SpermMar.pdf

Garolla, A., Pizzol, D., Bertoldo, A., De Toni, L., Barzon, L., & Foresta, C. (2013). Association, prevalence, and clearance of human papillomavirus and antisperm antibodies in infected semen samples from infertile patients. Fertility and Sterility, 99(1), 125-131.e2. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.006

Hamada, A., Esteves, S., Nizza, M., & Agarwal, A. (2012). Unexplained Male infertility: Diagnosis and Management. Int Braz J Urol, 38(5). Retrieved from https://www.brazjurol.com.br/september_october_2012/Hamada_576_594.pdf

World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research. (2010). WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen Fifth edition (pp. 108-110).

Zini, A., Fahmy, N., Belzile, E., Ciampi, A., Al-Hathal, N., & Kotb, A. (2011). Antisperm antibodies are not associated with pregnancy rates after IVF and ICSI: systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction, 26(6), 1288-1295. doi:10.1093/humrep/der074